I hoist my toddler son into a backpack, and walk into the thorny woods. There, surrounded by the farmland between Greensboro and Winston-Salem, I spot a sandy dry rill in the brush. We follow it over and under fallen pine trees. Charlie giggles and pulls on my ears as I swat away briars. Within minutes, we discover a small stream, then walk alongside it until it vanishes underneath a log. This spring is the beginning of the Haw River, which eventually will become the Cape Fear River. From where we stand, it’s 300 miles, downhill, to the Atlantic Ocean.

“Look, Charlie, water,” I say.

“Water,” he repeats.

The trickle quickly disappears into the woods, and we both want to know where it went.

I stood on a bridge near the tiny town of Moncure, 30 miles southwest of Raleigh. I could see water below. I just couldn’t get to it.

It was early April, and I’d carved eight days out of my life to paddle the entire 200-mile length of the Cape Fear River. I already knew some macro-level facts: It’s the only river in North Carolina that runs directly into the open ocean, draining an area the size of New Hampshire. Its basin provides drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people. But I wanted to see it up close, and paddle it to its end. Problem was, I lacked the basics. I didn’t have a kayak, I couldn’t find anywhere to camp, and I didn’t know anything about water quality or wildlife.

Weeks before the trip, I called Kemp Burdette, the Cape Fear riverkeeper, desperate for help. “You know,” he said, “I might be able to come with you.” When I called Chris Tryon, the co-owner of Hook, Line & Paddle outfitters in Wilmington, he quickly agreed to come and bring the kayaks. The outdoors photographer Andrew Kornylak also joined us, bringing a solar-powered charger to keep his cameras and our phones powered. I was in charge of picking the launch point, a boat ramp on the Deep River, three miles upstream from the Cape Fear.

When we arrived on day one of the trip, the ramp was locked behind a gate, surrounded by woods and “No Trespassing” signs. The nearby banks were steep and choked with brambles, trees, and poison ivy. I had assumed the river would be accessible wherever a roadway crossed it. Over the next eight days, I would learn that it never was. The river was not what I’d assumed it would be.

We sped toward a hastily Googled recreation area at the base of the B. Everett Jordan Dam. There, we filled up water bottles at a bathroom sink, carried hundreds of pounds of dry bags and boats down a rough trail to a muddy beach on the Haw River, and pushed off.

We saw squawking great blue heron, gliding osprey, and fluttering wood ducks. Turtles sunned themselves on logs. We passed tall oaks and leaning sycamores. A highway bridge appeared on the horizon. Chris, his bearded face shaded by a trucker hat and sunglasses, told me about his time in the Marines, what Panama and Iraq were like, how he got back to the States, and how he landed the business loan that got him his store. Kemp, with his short salt-and-pepper hair and fleece, was up ahead, pensively inspecting the bank, shouting back descriptions of what he saw. Andrew lagged behind, snapping pictures. Once we were all back together, Kemp looked up. “Pretty sure that was a bald eagle,” he said.

“Yup,” Chris replied.

One mile down, 199 to go.

This view — brown water, contained between green walls of trees, with a riverbend always in sight — would surround us for a week. There were slight variations: We would pass 14 road crossings. Four dams. Dozens of small boat ramps and hunting shacks. Hundreds of PVC pipes, stuck into the muddy bank to hold fishing rods. Scores of bush hooks — bits of fishing line tied to low-hanging branches — and “POSTED: No Trespassing” signs. There were factories, logjams, water intakes, drainage pipes, docks, downed trees, and mudslides. We saw an otter on day two, the first cypress tree on day three, a stray puppy on day five, alligators on day seven, and a dolphin on day eight. The water itself was swift at the beginning, glassy in the middle, and angry at the very end.

At times, we were the only people on the river for miles. We didn’t see a motorboat until halfway through day two. Except for Wilmington and Southport, we didn’t see cities or towns, no matter how close they were to the river on a map. Civilization was never far away, but it was almost always out of sight, sometimes heard, occasionally smelled.

None of us had ever taken a kayak trip this long. Kemp was here, a little bit, out of a sense of responsibility. “I’m the Cape Fear riverkeeper and I’ve never paddled the entire river,” he said.

Andrew wanted adventure. And pictures.

Chris thought of the Cape Fear as his home river, but also a prize. “To say you did a whole river, start to finish,” he said, “I kind of wanted to put that notch in my belt.”

Me? I thought back to my trip into the woods with Charlie. I simply wanted to follow the water. Forward. Downhill. To the sea. In doing so, I wanted to discover something. Sure, paddlers had traveled down the entire river before. But the number of people who had done it, let alone written about it, was small. Hence, the Cape Fear is well-known, yet mysterious. It is hard to know casually. Or in its entirety. On this trip, I could be something that few people get to be anymore: an explorer. I could understand the Cape Fear River in a way that few others do. But to do that, I would have to paddle it. All of it.

After four miles, we reached our first landmark: Mermaid Point, where the Haw meets the Deep, and the Cape Fear officially comes into being. We took pictures and ate apples. We tried to infuse this unmarked spot with meaning. The solemnity was tempered somewhat by roaring diesel engines and loud clanging as crews dismantled an old Progress Energy power plant nearby. Just downstream, Kemp paddled toward a rust-colored spot on the green bank, where chemicals seeped from a dormant coal ash pond nearby. Overall, the water quality of the Cape Fear wasn’t bad, but it could be better, he said. Rivers are good at collecting things we’ve forgotten about.

At Buckhorn Dam, a 12-foot-tall, river-wide wall with water pouring over its concrete top, we unloaded our boats, then pushed them up and over a vine-covered berm on shore. At Lanier Falls, one of many rock gardens with gurgling rapids between them, Kemp fell out, dumping his dry bags and coolers into the river, and shorting out his camp light. (He’d be unable to turn it off for the rest of the trip.) As the evening approached, the rocky outcroppings and 100-foot bluffs of Raven Rock State Park cast long shadows. We paddled to beat nightfall. As the last light of day faded beneath storm clouds over Lillington, we pulled our boats up a small asphalt ramp. Just then, the skies opened up, with lightning and pouring rain, and we sprinted toward the nearest shelter, Howards Barbecue. They agreed to stay open late so we could eat and dry off. Hush puppies, barbecue, black-eyed peas, catfish, beans, applesauce, okra, and chocolate cake disappeared in the blink of an eye.

As we paid our bill, a teenager in a ball cap asked us how far we planned to go.

“To the ocean,” I said.

His eyes widened.

The next morning, David Avrette came down to our little campsite behind his restaurant. “Son, this is eastern North Carolina,” he said, offering us free coffee, water, and bathroom use (indoor restrooms would be a luxury on this trip). He’d moved Howards to this spot, a cleaned-up auto junkyard, in 1992, and his father worried about him being down there in a hole by the river. You’ll get flooded out, he said. But David knew that Jordan Dam would protect him from the worst of the high water, and today, he owns the only restaurant within view of the Cape Fear on the 170 miles of river above Wilmington. Others may still be too scared to get too close.

After we paddled through Narrow Gap (“Go left,” was David’s only whitewater advice), we navigated our way through rocks, and followed wave trains until just past the Highway 217 bridge near Erwin. Up until that point, the Cape Fear was dropping an average of three feet in elevation every mile, and the resulting current gave us an extra two-mile-per-hour boost to our paddling. There was also plenty to see, and navigating the rapids kept our minds occupied.

Then, the water flattened.

When we started out, I’d believed The trip would be spiritual, but so far, it had felt technical. I’d brought along a new Moleskine journal to fill, but my wrists and fingers were tight. I could barely twist open a water bottle, and writing became physically painful. Instead, I tapped out notes and sent tweets from my iPhone. I never once lost cell phone service, shattering the image that I was truly in the wilderness. Once, I thought I heard Andrew talking to me from across the river. Turns out, he was FaceTiming with his family as he paddled.

On the second night, we had planned to camp at Old Bluff Church, a 158-year-old Presbyterian worship hall and cemetery that sat out of sight, at the top of a 100-foot bluff. It was serene, but terrible as a practical campsite. The take-out was unmarked, steep, and covered in poison ivy, and there was scarcely any flat ground to set up tents, let alone cook. The site would be a heavy struggle at the end of a 20-mile day of paddling, if we could even find it.

As we looked for a better campsite, an island appeared. Sandy, covered with trees, and separated from the bank by a dry channel, the pristine spot was the beginning of our streak of luck. River magic, we called it. We pulled ashore, and smelled the stench of chicken houses nearby. Soon, that smell was replaced by the scent of onions, garlic, and lentils wafting through camp from Andrew’s propane stove. Chris started a fire with his own private stock of oil-soaked firestarter.

Kemp was still astonished that we’d found this place. Most of the land that straddles the river is private, he said, which explains why only a small number of people have ever paddled the entire length of the Cape Fear. There was only one public campsite, back upriver at Raven Rock. This island camp was an improvisation, but Kemp had arranged the rest by calling friends and others he’d met as riverkeeper. Regular paddlers are mostly out of luck. They don’t have a Kemp.

There weren’t any “No Trespassing” signs on this island — the only sign of nearby humans was an overturned and unregistered johnboat — but we didn’t know who owned this property. I slept tentatively as the river gurgled. Chris snored loudly from his homemade hammock. Thankfully, nobody else showed up.

Fayetteville, also, never showed up. We’d heard the booms of artillery from Fort Bragg the day before, but as we crossed the city limits on day three, all we heard was the murmur of motors and honking horns in the distance. There were a few more people fishing, from boats and the shore, and for the first time, we saw men living underneath a bridge, with a small fire going. Farther down, a CSX train passed overhead on a trestle. An old World War II subchaser, which later served as a floating dock, sat half-buried in the mud on the bank. A rusting overhead crane and rotting wooden pilings were signs that barges used to make regular trips up from Wilmington decades ago. A small amphitheater at a riverside park and a marina were the only other clues that a city of 204,000 people was nearby. From the river, the volume was only slightly raised as we paddled through a green canyon, unable to see out. We floated past Fayetteville, and, quietly, it floated past us.

A steady wind gusted to 40 miles per hour. The kingfishers flying above us loved it, but the wind wrinkled the water and constantly blew our boats off course. I’d had the dumb idea to go barefoot, because I was tired of wearing soggy footwear. The wind quickly numbed my feet. My toes turned white. Andrew threw me a towel to cover them, but feeling and color wouldn’t return until the end of the day. From then on, I wore wool socks, covered in sandwich baggies, underneath my shoes.

After Fayetteville, we passed Interstate 95 and practically nothing else. A house here or camper there. A small creek or waterfall in between. As the evening closed in, we pulled up to a small dock as a couple of teenagers dressed in camouflage T-shirts loaded up a fishing boat. They were leaving to bait bush hooks — the next day, if the branch was bobbing, they’d know they snagged a catfish.

“That’s nothing like flood fishin’,” said Hughie Suggs, as we unloaded our gear on the dock. Last December, the river must have come up 40 feet at this spot, he said. Made for some great fishing in the flooded woods, because fish love exploring new ground, looking for food.

Hughie’s family has owned this land for generations, and soon, his neighbors arrived on ATVs to meet us. Hughie, a big man with a goatee, held his twin girls and told big stories in a cracking, singsongy tone. Once, he and some friends shot off a small cannon on a downstream sandbar, then got a visit from a game warden as they slept in their boats.

“I didn’t see no game warden,” Hughie said.

“He seen you,” his cousin replied.

Occasionally, kayakers pass through here, Hughie told me. Some of them say they’re going to paddle to the ocean with only a case of beer in their boats. Hughie tells them all the same thing: You’ll never make it.

At this point, I was convinced we’d make it to the end. But the rocky and rushing river of the early days had turned into an empty highway with no off-ramps. I chatted a little with Kemp, Chris, and Andrew, but I learned that a long, thoughtful conversation could mess with the rhythm and intensity of our paddling, and eventually, we’d drift apart. By day four, I zoned out for hours at a time, humming to the rhythm of my strokes. I stared, hypnotized by the blue cooler between my knees. Fallen trees were no longer unusual, gnarled logs were no longer curious, flapping ducks were no longer startling. Nature was no longer new. It was normal.

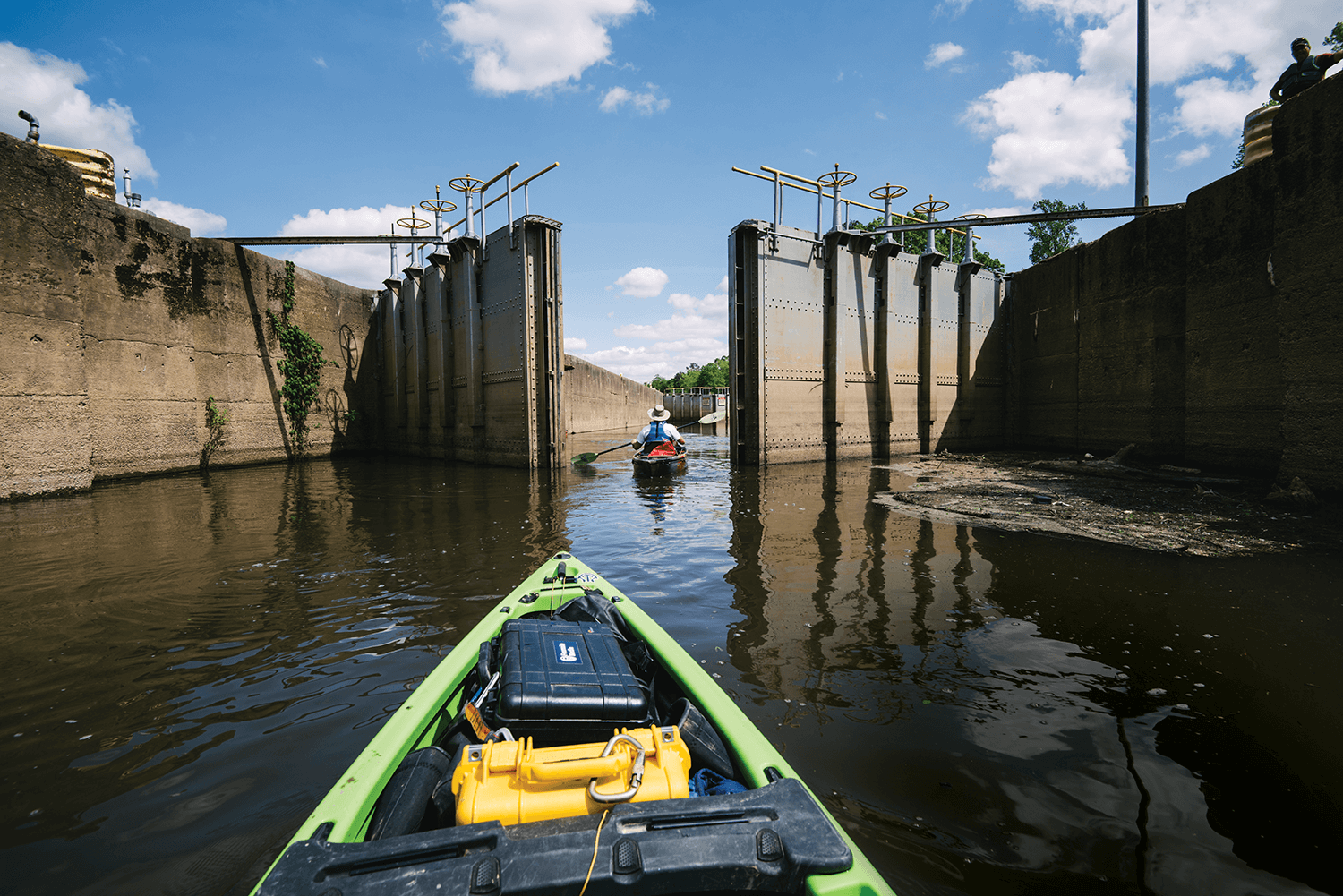

Before we reached the William O. Huske Lock and Dam in Bladen County, we’d been hoping the lockmaster would operate the lock for us, to save us from having to carry our boats and gear over several hundred feet of dry land. But as a result of budget cuts and a lack of traffic, the locks barely ever open anymore. Still, we got lucky. As we ate lunch at a picnic table near the dam, Chris saw a friend who’d driven up from Fayetteville to fish for striper and shad here. He got the friend to carry all of our gear around the lock in the bed of his pickup truck.

And later, river magic struck again. We stopped at our campsite, fully expecting to spend another night in the woods, when the landowner’s father, Frederick Tate, pulled up on an ATV and whisked us away to his son’s weekend getaway, a rustic house with a beautiful kitchen and hot showers. The great irony: All we had to eat was freeze-dried food, so we only used the expensive gas stove to boil water.

The following afternoon, as we passed Elizabethtown, our trip’s halfway point, we sniffed the fishy smell of shad and bass spawning beneath us. We stopped at Lock and Dam No. 2, where an old fisherman with a big net asked us if we were “fishin’ or funnin’.” I walked up a road to the edge of a farm field. After days of tree-tunnel claustrophobia, with our voices echoing off greenery, the wide-open space was as soothing as white noise.

We figured we were going to have to carry everything around this lock, too, until Kemp spotted an Army Corps of Engineers pickup truck. The lockmaster was here, and Kemp started giving the man his best sales pitch. The lockmaster stopped him. “You guys want locked through, don’t you?” the lockmaster said. The doors closed. The water lowered. Ten minutes in the lock saved us an hour.

After the second dam, the river wound more sharply. The banks were lower. The trees were shorter. There were more loblolly pines and bald cypress. There were fewer eagles and more songbirds. More snakes and fewer turtles. It was a subtle change, one that we wouldn’t have even noticed had we not already been paddling for five days. Our sense of distance also had changed. A highway mile is a minute long. But a river mile, on flat water, takes roughly 25 minutes and 700 paddle strokes. On the 10-mile stretch between the lock and our campsite, I kept thinking our destination was right around the corner. We ended up saying “we’re almost there” for three and a half hours.

That night, we sat around a campfire on a large white sandbar, cracked beers, and talked about the nature of river time. Somehow, Chris said, we’d been paddling five days, and covered 114 miles, yet “Jordan Dam doesn’t feel that far away.”

“It’s not the same kind of feeling of time that you get during the workweek,” Kemp said. “Seems like we’ve been doing this for a while, but it doesn’t seem like we’ve been doing it for very long at all.”

We talked into the night, as stars twinkled overhead, owls hooted, and fish jumped in the dark river. At that moment, we had all the time in the world.

The next morning, I woke up at 6, with rain pitter-pattering my tent. We’d long been dreading today’s distance (30 miles) and weather forecast (steady rain). But by now, we were paddling robots. We broke camp at 7, passed the two-car Elwell Ferry by 11, and approached the final lock at 1:30. Here, we saw streams that the Corps had dammed up to keep the water from cutting a new route around the dam. Even though the hundred-year-old lock is barely used anymore, the Corps can’t remove it because there are drinking water intakes right next to it. Instead, engineers have dropped boulders below the dam to create rock arch rapids, allowing fish to swim upriver to spawn.

Past here, the river, and our paddling, would be affected by the tides, so the closer our camp was to Wilmington, the better. We had planned on staying near a golf course by International Paper’s massive mill at Riegelwood, which smelled like wood chips and sulfur. We kept going. After 10 hours of paddling, we weren’t tired. We were just warmed up.

We pressed on for five extra miles before pulling up at a landing. As we started to set up our tents and dry out our gear underneath an orange sky, an oversize Ford pickup emerged from the woods. A white-bearded man stepped out and told us his wife simply wouldn’t allow us to camp down here. She demanded that he bring us all back to the house to sleep indoors. Soon, we were whizzing through the dark woods in a truck bed. More river magic.

The man, Archie McGirt, told me his story. He and his wife had lived on this land about 16 years, but he’d been around the river his whole life. “I see everything that moves, crawls, wiggles, or swims,” he said. He doesn’t need pictures. “If I want to visualize Horseshoe Bend or Bald Head Island, I close my eyes.”

I nodded. This week, I’d stopped living my life through a smartphone stream. Everything felt vivid, as though my brain was learning, once again, to form memories.

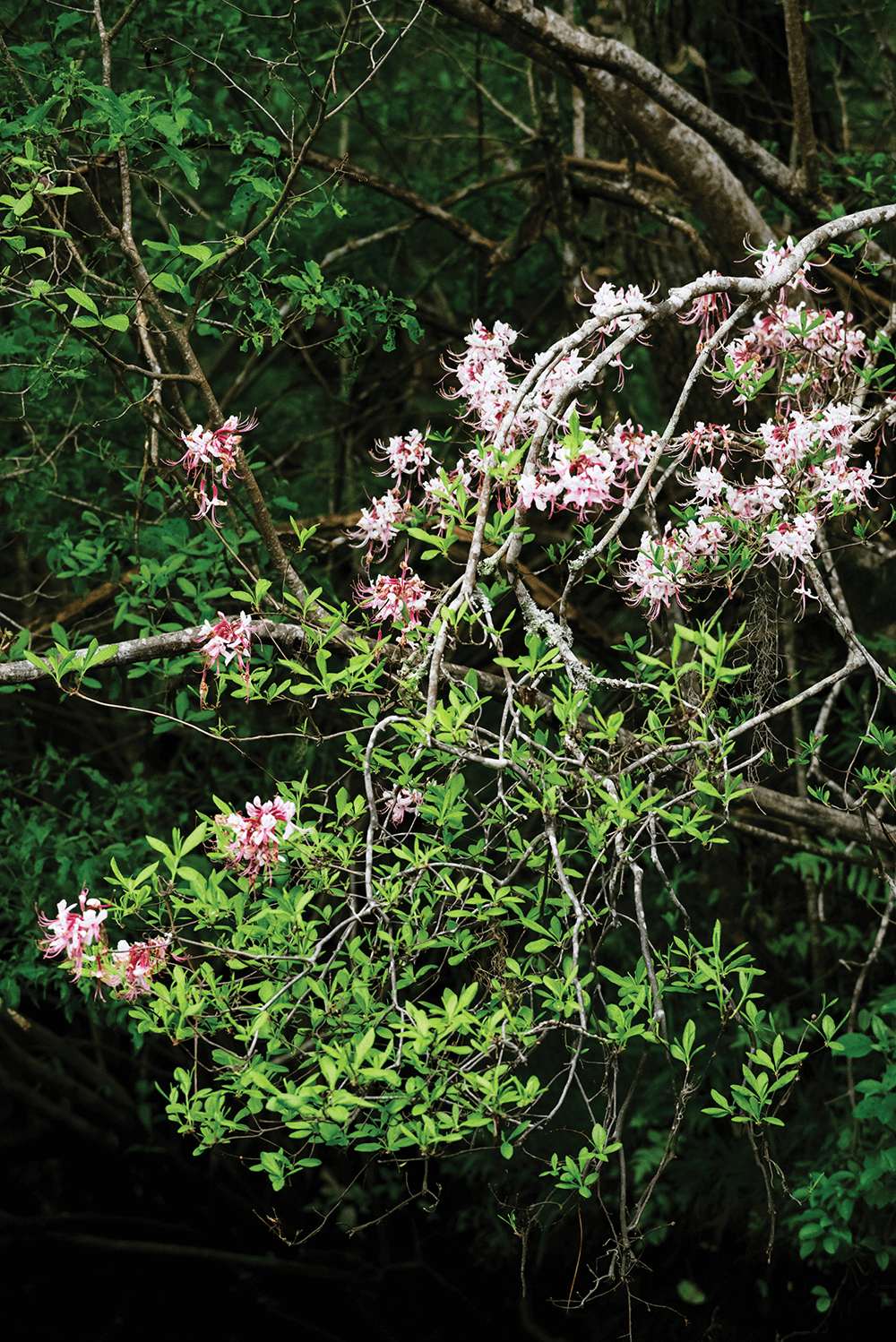

The next morning, the purple-and-orange sunrise revealed a strange new landscape: swampy, full of palmetto and native azalea. Every bit of ground was soggy. The cypress trees were marked with dark water lines, evidence that the high tide was rushing downriver toward the ocean. We’d gotten up at 5:30 to ride the current down into Wilmington, and the water pushed us to a top speed of 5.3 miles per hour. We passed Roan Island, and the aptly named Black River. Soon, seaweed appeared, and fiddler crabs scurried in the mud among the spartina grass. Chris and Kemp disappeared ahead, and Andrew was gone, too, somewhere behind me, taking pictures. For the first time on the trip, I was alone. On a kayak. Drifting through the swamp on a falling tide.

The seclusion was an illusion. I was four miles from the closest town. I’d been able to hear cars on Highway 87 for the past two days. I’d called my wife and Charlie every night. The map and the signal on my phone showed me that I was on my own, yet close to everyday life. I was unable to be seen, yet always within reach. The Cape Fear River was only as private as I wanted it to be.

At 10 a.m., Andrew caught up, and we passed the Sutton power plant. As the river turned, the trees that had enveloped us melted away. Suddenly, we were in a brown, open expanse, with sunshine all around. Dead cypress trees, killed by the ever-increasing intrusion of salt water, cut stark figures against the blue sky. This was foreign. Alien. The four of us reunited at the under-construction Interstate 140 bridge, as construction workers soldered rebar high above. Ahead, the church spires and office buildings of Wilmington rose above the grass like a mirage. They were four miles away, and the farthest things we’d seen in a week. For so long, we’d only been able to see to the next bend.

We ducked underneath a railroad bridge at Navassa as a large sightseeing boat was bearing down on us. “We love you, Kemp!” screamed a dozen women and girls onboard. Kemp shook his head and smiled. The captain was a friend of his, Kemp said. He wasn’t really that popular.

At 11:30, we paddled underneath another highway bridge at the mouth of the Northeast Cape Fear River, and suddenly we were downtown, passing a Coast Guard cutter and the Battleship North Carolina, waterfront parks, buildings, fountains, and cars. Men and women eating lunch at riverside restaurants watched us take stroke after stroke. Joggers glanced at us. Dogs sniffed in our direction. We sat up straight, and stuck out our chests. We paddled toward Dram Tree Park like runners entering a stadium at the end of a grueling marathon.

We turned left, just above the noisy Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, and pulled onto a ramp, where Cape Fear River Watch volunteers, friends, and onlookers greeted us. We walked up the street to Elijah’s for a big lunch and Endless River beer. It felt like our journey was over, even though we weren’t done just yet. “The worst part of the trip ending?” Chris said. “You don’t get to paddle the next day.”

As we walked, one of the onlookers stopped me. “How was the trip?” she asked.

It was like having a new job, I said. A good job. I got up in the morning, and got to work paddling. At the end of the day, I had dinner, relaxed, and went to bed. The next morning, I got up and did it again. It was simple. As simple as I dreamed it could be.

And with that, on the seventh day, we rested.

The last day of paddling was an afterthought. We had 26 miles to go, and the wind was at our backs, with a falling tide to push us. We’d reach the river’s end by lunchtime. We left Dram Tree Park at 5:30 a.m. with light boats, carrying just some water and snacks. We paddled into the blackness of the 42-foot-deep shipping channel and quickly encountered a container ship, the Maersk Wakayama, being guided by a tugboat to the mile-long State Port just south of downtown. We gave it a wide berth. The ship was almost the size of two football fields and its captain likely couldn’t see us.

The Cape Fear River was now an estuary, and as its water dried on our coats, it left behind a salty residue. The channel was a mile wide. We passed Island 13, a splinter of land bulked up by sand and dirt dredged from the riverbed. Ahead, the water disappeared into the horizon, under a blue sky flecked with high, pink clouds. Pelicans, ibis, and seagulls circled above us. It was a lovely morning.

Then, the sky turned gray.

As we started to paddle past Military Terminal Sunny Point, crossing over toward the west side of the channel, the wind pushed water at us from all sides. I felt the raw power of the ocean crashing toward me. Three-foot swells jostled our little boats. The waves turned the kayaks from side to side, and crashed over our bows. In the middle of the channel, it was impossible to tell if we were moving forward. The tide would soon turn and begin pushing harder against us. We had 10 miles to go, and four hours to get there. If we didn’t make it to the end by then, we might be stuck out here.

The river that had held me in its cozy embrace over the past seven days was gone. All around me: barges, Panamax tankers, and shrimp trawlers plowed through the water with ease. I worried that the wrong wave might capsize my open-top boat, and I would be an unseeable speck in the angry foam — a mile of water in every direction. I kept going, futilely, drawing a straight line, paddling toward Kemp and Chris ahead of me, trying not to drift toward the ominous warning signs on poles in the water around Sunny Point, where gunboats patrolled near the shore in the distance.

For the first time, I wanted this journey to be over. I had overstayed my welcome. I was scared.

Eight days ago, this river had been a blue vein on a map. Ever since I’d slid my kayak into the water at Jordan Dam, the river and I both moved, slowly and purposefully, toward the ocean. I became comfortable in its grip. Its water was always beneath me; its banks always surrounded me. Now, it was telling me that it was time to go. The Cape Fear River was a story, and this was its climax. The story would be over when its water, which once had such purpose, was cast into the infinite sea. I had set my sights on the open ocean, now just two miles away. But I knew I’d have to stop before I reached it.

I looked ahead, through the spray, and saw the Atlantic to my left, and the Oak Island Lighthouse to my right. I aimed my boat at the blinking light, toward Southport, and paddled hard. My destination, finally, was in sight.

I passed underneath a long industrial dock, and reunited with the team in front of the Price’s Creek Light. Instantly, the water calmed, and blue sky poked through the clouds. The Bald Head Ferry honked at us as we rounded a gentle curve and passed houses and dozens of docks stretching into the water. Just before 11:30, our boats skidded into the sand on a small beach, in front of a row of houses on West Bay Street in Southport. Our journey down the Cape Fear was over.

After nearly 200 miles, the ending was short-lived. Within an hour, we’d all be heading home to our families. Still, it was Chris’s 40th birthday, and over lunch at Provision Company, we raised a toast to him, and to all the people who told us they’ve always wanted to paddle the entire Cape Fear River. Chris and Kemp both admitted that this trip wasn’t as spur-of-the-moment as I’d first thought. “We’ve been talking about doing it for two years,” Kemp said.

I asked what had held them up.

“Life,” Chris said.

The next day, I was at a park with Charlie, 300 miles away, not far from the spring we’d found in the woods months before. I’d just seen where that trickle of water ends up. I still couldn’t shake the feeling that I wasn’t the explorer I thought I was going to be. I’d finished something big, but for eight days, all I’d done was go forward. I hadn’t discovered anything.

Or, maybe I had. The river wasn’t really big. It was small. Subtle. Its subtlety was David Avrette’s coffee. A sandy island campsite. Hughie Suggs’s stories. Frederick Tate’s ride to breakfast. A lockmaster in the right place at the right time. A turtle slipping into the water. The soft noise of nature. The early morning sunlight dancing in the rippling water.

I’d made three new friends. I’d discovered what I was capable of. I’d found river magic all around me — just not where I’d been looking.

Charlie and I followed a trail through the park and came upon a pond. He pointed.

“Water,” he said.

“Water,” I said back.

Here’s how we paddled the entire length of the Cape Fear River — and what we saw — during our eight days on the water.

Four men who barely even knew each other met in-person for the first time on the day before the trip began. After eight days together, they finished the journey as friends.

Jeremy, Andrew, Kemp, and Chris documented their trip in real-time via Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can find their chronological recap of the trip here.

Photographer Andrew Kornylak took nearly 6,500 pictures over eight days on the river. Of them, 48 appear in November’s print edition of Our State magazine. Below, some extra pictures, and an explanation of Andrew’s strategy for photographing a 200 mile kayak trip.